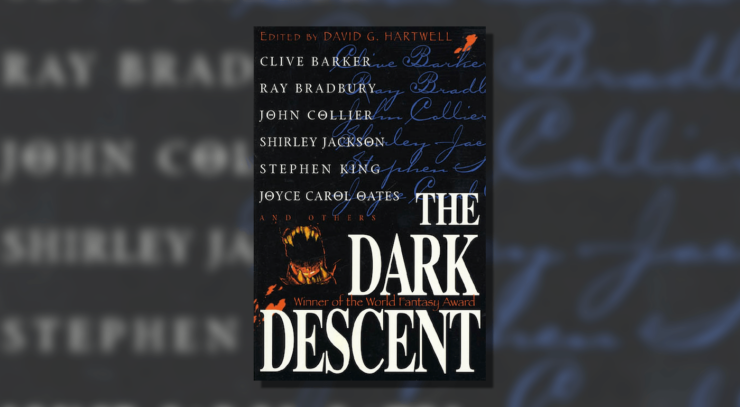

Welcome back to Dissecting The Dark Descent, where we lovingly delve into the guts of David Hartwell’s seminal 1987 anthology story by story, and in the process, explore the underpinnings of a genre we all love. For an in-depth introduction, here’s the intro post.

Walter de la Mare is once again proof that we shouldn’t let poets and children’s authors write horror fiction; they’re far too good at it. While de la Mare’s main stock and trade trended more towards poetry (he edited several anthologies) and children’s stories, his supernatural stories could be said to be his most influential works. He’s a horror writer’s horror writer, with fans including most of the authors featured in The Dark Descent—everyone from Campbell to Aickman to Lovecraft counts him as an influence. His gift for the abstract and unnerving serves him well in “Seaton’s Aunt,” taking the story of a strange, withdrawn boy and his abusive relative and turning it into a twisted, gothic work of psychological suspense. In the process, “Seaton’s Aunt” explores power, powerlessness, and the horror that comes from an all-encompassing torment.

Withers is a boy at Doctor Gummidge’s boarding school the first time he meets Arthur Seaton. The other boy is odd, with an off-kilter appearance and a mysteriously large allowance he receives from an eccentric aunt. Despite Seaton’s unpopularity, he and the seemingly more gifted Withers fall in together, Seaton eventually inviting Withers to his home to meet his mysterious aunt. An odd woman with a strange bearing and rather large head, Seaton’s aunt delights in playing the boys against each other and engaging in odd displays of power over them, further unsettling Seaton as she does. But are her mind games simply the bizarre whims of an older woman, or evidence (as Seaton suggests) of darker and more sinister forces at work? The answers will haunt Seaton and Withers for the rest of their lives.

For all David Hartwell spends his introduction to “Seaton’s Aunt” discussing the concept of “uncertainty,” the moment Seaton’s aunt appears, it’s clear that the story is one of abuse. She’s a grotesque creature, cloying and gluttonous in every respect, a twisted, nigh-omniscient beast who barely counts as human. The further the story goes, the more grotesque and inhuman she gets, transitioning from a strange old woman into something that could feasibly be found in the darkest recesses of Jim Henson’s Creature Shop. The control she exerts over her house and over Seaton is total, not just in the way she spends every single moment tossing insults at her nephew over piles of greasy food but in the way that he tends to vanish from scenes with her even when he’s present. Her interest in Withers, the narrator of this sordid tale, is mainly to further put Seaton down, using a time-honored technique of asking someone about their accomplishments in order to passive-aggressively batter a chosen victim.

This extends to Seaton, whose sallow and unusual appearance, bid to buy friends with expensive gifts, wanton spending, and quiet, withdrawn behavior all speak to trauma at home. Seaton is literally set apart from the “normal” students at Gummidge’s both in personality and appearance, constantly being described as “fish-eyed” and “foreign,” talking barely above a whisper. Withers frequently takes note of this in his narration, describing how Seaton is always apart from and alien to the other students and to Withers himself, even as he describes Withers as “his closest friend.” One of the effects of long-term abuse, especially psychological and emotional abuse, is to alter the victim’s mental state to the point that they’re alienated from those around them just by an ingrained sense of strangeness. With Seaton, this strangeness makes him pathetic, a target for abuse by the other boys at Gummidge’s and a pitiable unwanted companion for Withers. The external torment reinforces the internal torment, further marking Seaton as someone who is “wrong,” a conclusion no doubt helped along by his insistence that his aunt is an omniscient, omnipresent sleepless entity in league with demonic forces.

All of which makes Withers an unwitting but active participant in Seaton’s humiliation and abuse. Withers either doesn’t notice or pretends not to notice exactly how off everything is—one scene has him realizing that the aunt beat him at chess but refused to deliver a checkmate, instead claiming a draw and complimenting Withers on his play, leading to a confused Withers being berated by Seaton for “not playing harder” or letting her win. Withers’ politeness and the aunt’s twisted hospitality are also weaponized against Seaton, with the aunt acting just nice enough that Withers doesn’t completely catch on to her true purposes and answers her questions truthfully, Seaton shrinking into the background the more his aunt humiliates him.

Withers’ unwitting complicity in events (it’s possible Seaton brought him back for the holiday so his terrifying aunt would have to play nicer, as a common tactic to control an abusive situation is to force the abuser to be sociable with someone outside the dynamic, only for things to backfire) also causes him annoyance when Seaton tries to show him that the aunt moves around during the night and insists that there are strange presences haunting the house. It’s only at the end of his visit when he starts to catch on—the aunt’s toying with him and lets the mask slip just enough to make it obvious what she’s doing. From this point in the story forward, “Seaton’s Aunt” becomes less a story about the nature of Seaton’s unusual relative, and more about the aunt’s effect on Seaton and everyone around her. By the time Withers sees Seaton again, the unfortunate young man is engaged to a young woman named Alice, and it’s clear that the aunt sees both as unwilling players in her little power games, free to do to them both whatever she’d done to Seaton.

The unsettlement in the story takes center stage in this section. As previously stated, the abuse is clear enough that anyone who’s been in Seaton’s situation can see it. The horror comes not just from Seaton’s victimhood, but from the totality of his aunt’s control. With that gleeful little exchange between Withers and Seaton’s aunt, suddenly the questions left unexamined in the first half of the story and unanswered in the second half bubble up: Was Seaton’s purported inheritance real, or just another lie to control him? Did his vile aunt really bump off his parents, or is it simply a very strong possibility? And, as she seems to remain relatively the same over the decades, what is Seaton’s aunt? These questions and their lack of definitive answers are the crux of de la Mare’s sense of unease, adding an aura to Seaton’s aunt that extends outward to everything within her sphere of influence, a corruption affecting all those caught in her orbit. Alice and Withers manage to escape, but unfortunately, it’s too late for Seaton. As is the case throughout the story, Withers, the one person who could possibly intercede, realizes too late and is left with a sense of disquieting guilt as he pointedly avoids a visit to Seaton’s grave.

For those unable to leave a toxic relationship or environment, that sense of unsettlement, of wrongness, is total and all-encompassing. Whether or not Seaton’s aunt is an actual supernatural force or one is simply projected upon her by her abused and traumatized nephew is academic—the threat she represents and the damage she does is all too certain. By introducing gothic horror elements into a story of psychological and emotional abuse, de la Mare both heightens the horror of Seaton’s torment and turns Withers’ unwitting complicity and bystander status into something far darker than that of a mere observer. It’s a terrifying study in power and powerlessness, one far too many know all too well.

And now to turn it over to you. What is Seaton’s aunt, really? Could Withers have stopped her? Was there anything supernatural in the story, or merely the overactive imagination of two young men?

Please join us next week as we dig into the work of Tolstoy’s most famous rival with Ivan Turgenev’s “Clara Milich.”